Mice, men, and the need for speed.

Two ways of looking at an interesting discovery.

Every now and then I read an off-hand sentence, buried in the middle of some article, that my brain keeps picking at for days or weeks. Today's example is from Science News, in an article titled Semaglutide saps mice's motivation to run. It covers a paper by Ralph DiLeone and collaborators at Yale, who were studying side effects of semaglutide, a drug developed for diabetes, but commonly prescribed for weight loss.

DiLeone explains that mice are distance runners, riding their wheels as much as ten kilometers a day. But a week of semaglutide cut their average distance by 38 percent. The team compared these mice to another group who lost weight through diet control and kept on running their accustomed marathon. With this and a few other experiments, the paper suggests a link between semaglutide and a reduced motivation to exercise. The article then asks what should be done if the result holds true for humans. Neuroscientist Karolina Skibicka suggests, "Doctors might need to change how they talk with patients about these drugs, saying, 'Hey, you might feel like you don’t want to exercise, but it’s really important that you do.'"

And then, down there near the bottom, there's this one little quote from DiLeone:

"It is possible that the mice are also exercising compulsively."

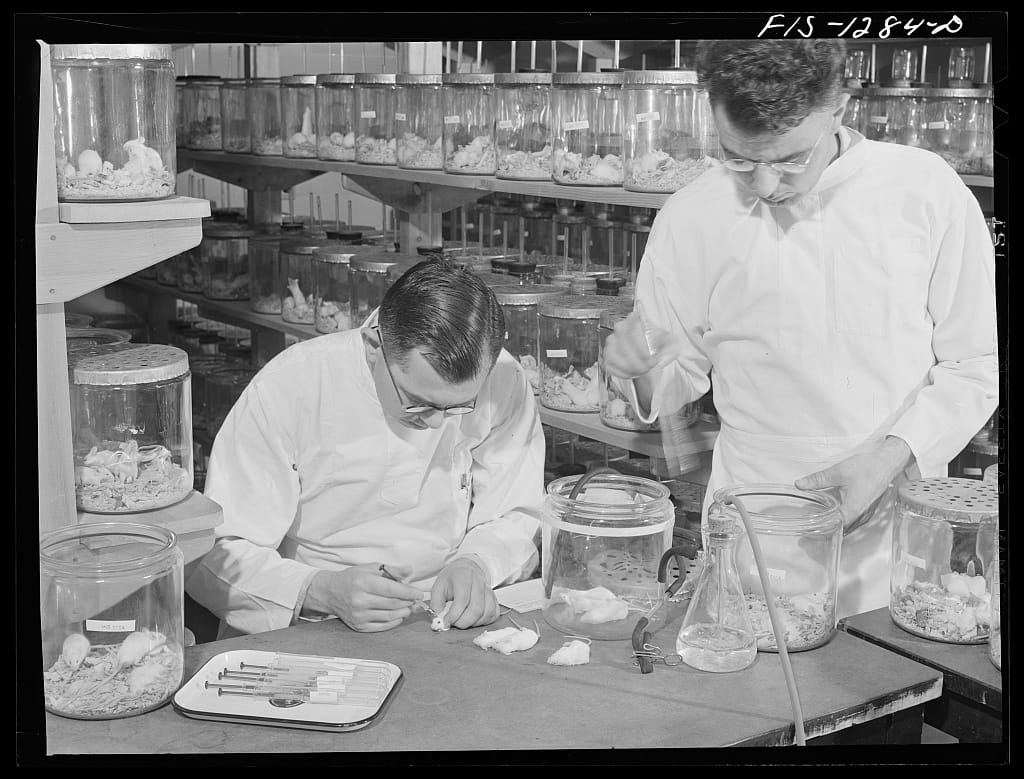

See, in other research, semaglutide has been shown to reduce compulsive behavior, to the point that it's being studied as a treatment for addiction. So another plausible explanation is that all the mice in all the cages in all the laboratories everywhere are spinning their wheels in response to some uncomfortable compulsion, rather than a zeal for running, and these researchers accidentally helped them feel better. This isn't a wild theory, either. There's an old, famous study that I won't bother looking up, which showed that mice with a choice between cocaine and food will always choose the cocaine, even to the point of starvation. This study was repeated in various places, and became accepted fact. Then, in 2015, some folks at the UC Berkeley tried a modified version of this experiment, with mice who were allowed to live like mice. They discovered, surprise surprise, that mice who were given mousy things to do, like exploring corridors and digging for treats, were less excited about cocaine, and often ignored it entirely.

It's totally possible that all these lab mice are scared and stressed, and their instinct says "run!" Or maybe they're just bored off their little gourds. And maybe semaglutide lets them chillax for a minute. In fairness to DiLeone, it sounds like his team is looking into the compulsion possibility, so it's not unthinkable that they'll change the way we study laboratory mice.

Yet the "semaglutide saps motivation" angle is a pitch that no reporter can help but swing at. It fits our expectations too well. In popular culture, weight gain is a personal failing, and weight loss is something you earn. A weight loss drug is, at worst, a kind of cheating, or at best a naïve pipe dream. If a pill is the lazy man's path to weight loss, news that the pill could make him lazier is appealing to our sense of just desserts.

For now, no one knows if semaglutide makes people less eager to exercise. If it does, we'll have learned something useful. Either way, we should persist in asking whether it's the pill or the cage that deserves the greater scrutiny.